Do Teacher Incentives Improve Learning Outcomes? By Silvia Montoya

By Silvia Montoya, UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) and Jordan Naidoo, UNESCO

Over the past decade, many countries have increased their spending on education as a share of gross domestic product. Between 1999 and 2012, public expenditure on education grew by 2 to 3 percentage points in such diverse countries as: Benin, Brazil, Kyrgyzstan and Mozambique, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). Yet this investment has not necessarily led to improvements in academic performance, according to international assessments. This inevitably leads to questions about school trajectories and how to ensure that all children acquire a quality education and the skills they need as adults. From curriculum reform to school infrastructure investment, there are many options to consider, but in the end they tend to focus on teachers, with discussions revolving around wages, evaluation and performance pay.

Over the past decade, many countries have increased their spending on education as a share of gross domestic product. Between 1999 and 2012, public expenditure on education grew by 2 to 3 percentage points in such diverse countries as: Benin, Brazil, Kyrgyzstan and Mozambique, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). Yet this investment has not necessarily led to improvements in academic performance, according to international assessments. This inevitably leads to questions about school trajectories and how to ensure that all children acquire a quality education and the skills they need as adults. From curriculum reform to school infrastructure investment, there are many options to consider, but in the end they tend to focus on teachers, with discussions revolving around wages, evaluation and performance pay.

Dispelling the myth: Teachers’ salaries are neither high nor low

Everyone seems to have an opinion about teachers’ salaries, which can account for 80% of education budgets according to UIS data. In some countries, teachers are highly skilled but underpaid. In others, it is claimed they are overpaid given the poor results of their students. To better inform the debate, we should start by asking which figure should be used to compare teachers’ salary levels.

In a study for the European Commission, Fredriksson (2008) compared the salaries of primary school teachers with 10 years of experience with different types of skilled worker professions. The author found that, in most of the 29 European cities with available data, a teacher earned less than the first six types of skilled workers but more than the others. In short, the study shows the limitations of trying to decide whether a teacher earns too much or too little in debates about student performance. There are no highs or lows – just individuals or groups of individuals working in very different circumstances and societies.

Incentives and pay per performance

For some analysts, economic incentives based on student outcomes are the means to improve teaching. Part of the problem with this proposed solution lies in establishing the results to be measured. Teachers provide services to stakeholders with different expectations: from the school principal to the students, parents, taxpayers, politicians, etc. Each group has a different view in evaluating the quality and performance of teachers.

To simplify matters, many education systems rely on student assessment tests to evaluate teacher performance. Yet it is very difficult, if not impossible, to accurately measure all areas of learning. We must also recognize the cumulative nature of the educational process: the skills acquired by a child in a given year do not just reflect the performance of the teacher being evaluated. And surely we must consider the impact of a child’s wider environment (home and community). To what extent does socio-economic status affect a student’s performance?

Given the complexity of education systems, explicit incentives for teachers may do more harm than good for students in terms of their learning outcomes (Fehr and Falk, 2002). This may explain why academic results of students do not necessarily improve with performance pay, where a teacher’s salary increases in relation to an outcome, such as student scores in a standardised test. Money may not be all that matters in the education sector (Steele, Murnane and Willett, 2010).

Motivation and incentives

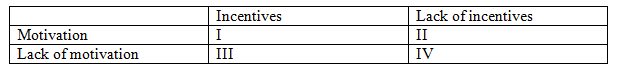

The current debate around performance pay ignores non-pecuniary motivation, such as the pleasure in teaching students. Economic incentives may be necessary but do not ensure love for the profession. So it is essential to consider the possible linkages between motivation and incentives as presented in an oversimplification in Table 1, given that intrinsic motivation could have many aspects and in addition there are multiple incentives.

Table 1. Combination of motivation and incentives

Source: Montoya, 2014

The ideal situation is presented in quadrant I where the intrinsic motivation and the reward are aligned. The worst case scenario in quadrant IV with no motivation and no incentive there is no effort. In the intermediate situation of quadrant II, the teacher is motivated to get results but lacks incentives to sustain the momentum over time. In quadrant III, there are incentives but they do not work because of a lack of motivation.

Part of the problem with the performance pay approach is it assumes that teachers alone are responsible for student performance. To be fair, it must also be linked to clear incentives for the student. After all, there is a limit to the teacher’s ability to motivate students.

For example, many teachers make tremendous efforts with students, especially from vulnerable or high-risk groups, but don’t necessarily see the results in assessments. Every country has highly-qualified teachers frustrated by unmotivated students or the opposite situation with motivated students confronted by unskilled teachers. How can we identify these dynamics based on a test result?

Teachers are part of the solution not the problem

Assessment results also don’t show the non-pecuniary motives, such as the desire to teach and the sense of social justice, which can drive the efforts and results of teachers.

According to the 2013 Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), some countries revealed that 90% of participating teachers loved their jobs despite some difficult working conditions.

On the positive side, teachers working in collaborative environments, allowing for exchanges of ideas, reported higher job satisfaction and confidence in their abilities. The issue lies in the egg-crate schooling model[1] where many work in isolation. More than one-half reported that they rarely or never work as a team, and only one-third had the chance to see how their colleagues teach.

Secondly, TALIS reported that 9 out of 10 teachers agreed that performance appraisals led to positive changes as long as the evaluations were not simply treated as an administrative requirement (which seems to be the rule). Yet 46% of teachers reported that they have never received any feedback from their school principal.

Overall, research shows that teachers are the most important influence in schools on children’s learning. So instead of trying to punish or reward them through salary schemes, perhaps we should take the lead from their personal inspiration in joining the workforce.

In 1939, Julio Cortázar (2009)[2], an Argentine writer and teacher, spoke of the challenges in his address to the graduates of a teacher training institute: “Those who have studied to become a teacher without really knowing what they want or expect beyond the position and the monetary benefits have already failed”. But for those devoted to the mission of teaching, “the sacrifice will make them happy. Because in every true master we find a saint”.

Silvia Montoya (@montoya_sil) is the Director of the UNESCO Institute for Statistics. www.uis.unesco.org

Jordan Naidoo is the Director of Education for All and International Education Coordination at UNESCO

>>View all NORRAG Blogs on Teachers

NORRAG (Network for International Policies and Cooperation in Education and Training) is an internationally recognised, multi-stakeholder network which has been seeking to inform, challenge and influence international education and training policies and cooperation for almost 30 years. NORRAG has more than 4,200 registered members worldwide and is free to join. Not a member? Join free here.

[1] The egg-crate schooling model refers to the stacking of one change on top of existing structures.

[2] Cortázar, J. (2009). Papeles Inesperados. Alfaguara. Buenos Aires, Argentina.