‘Big Data’ Does Not Mean Good Data By Susan L. Robertson

By Susan L. Robertson, University of Bristol.

Andreas Schleicher – Head of the Indicators and Analysis Division in the OECD, Paris, in his many presentations on the now famous Programme of International Student Assessment – or PISA – likes to conclude with the phrase: “Without data, you are just another person with an opinion”.

Andreas Schleicher – Head of the Indicators and Analysis Division in the OECD, Paris, in his many presentations on the now famous Programme of International Student Assessment – or PISA – likes to conclude with the phrase: “Without data, you are just another person with an opinion”.

Now this is an extremely powerful claim, not only just because it aims to locate data at the centre of what might count as ‘truth’, but because it is also a particular kind of data: numbers and quantification. And what is equally as important here is that a small group of data framers and brokerage merchants – which now includes the OECD, the World Bank, Brookings Institution and Pearson Education, are increasingly located at the global level beyond the spaces in which education politics and policies are debated by the profession and the wider public.

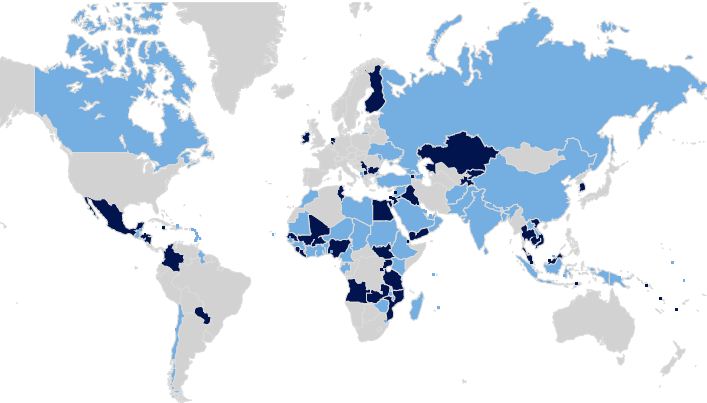

The World Bank’s entry into the business of ‘truth’ gathering is also by way of collecting global data sets on various aspects of education. In 2011 it launched SABER – Systems Approach for Better Education Results, and is now in various stages of data collection and reporting. Thirteen areas of education have been identified, ranging from teacher policies, to policies on school finance and student assessment. Unlike the OECD, who collects data on student performance and teacher characteristics, the Bank has chosen to collect data on system policies as evidence these practices exist, and which in turn are assumed to create better student outcomes.

Yet the Bank has a highly normative, or dare I say ideological, view as to what counts as a good education system. It is one that favours education as a consumer good, where limits are placed on state monopolies of education, that are open to the for profit sector in what many regard as core business, and which introduces incentives for better teacher and student performance. Using data collected from national systems, the Bank then charts the levels of progress toward this assumed ‘best system of education’ around judgements as to where along this path the country is currently located – as ‘latent’, ‘emerging’, ‘established’, ‘mature’ and so on. Reports are then produced for the participating country, which includes comparisons with other countries who are participating in the round of data collection.

However there are huge limitations in the SABER instruments; it all too clear that the gap between policy artifacts and policy practice is more than chasm-like. Take, for instance, SABER-Teachers, one of the Bank’s 13 SABER instruments – and the Bank’s account (in the form of a report) of Cambodia, one of the countries in their SABER-Teachers Project. The Bank offers a reasonably favourable view of the level of development trajectory of teacher policies. However, as researchers of Cambodia will point out, this picture that is painted is hugely different from education on the ground.

To be sure, there are policies in place, but this is where it begins and mostly ends for many teachers. A policy is a promise, or in this case a policy fantasy to be realized. But still a fantasy. In reality, many teachers in Cambodia – particularly in rural settings – are often in highly precarious situations with regard to their conditions of work, their wages, class sizes, and far too comfortable a relationship to the market and the excessive commodification of almost all aspects of the education experience. Yet we are told in the report card on Cambodia that teachers have conditions of work that are very appealing (rated ‘established’) though teachers are likely not to be trained according to particular standards or indeed receive ongoing professional development (noted as ‘latent’). Students are also closely monitored (implying a link back to effective teaching) through examinations, yet again as researchers on Cambodian education show – the examination system is rife with corruption, and it is the shadow education system that matters most (and which students have to pay for) which determines student outcomes.

Now the difference between policy and practice opens up even further in that there is a yawning gap between the formal education system which the Bank is reporting on, and the shadow system that sits out of sight but which is central to understanding student performance and teachers’ work.

Now this is not the place to log on an account of the issues facing the Cambodian education system. But, it is a useful example to show that Schleicher’s confidence in data is not just misplaced, but somewhat ambitious. For surely what is at issue here is that big data can be big bad data, just as some data can be bad data. Big simply magnifies the margins of error. And for the Bank and its SABER-Teachers project, these seem to be huge.

Professor Susan L. Robertson is the Director of the Centre for Globalisation, Education and Societies, Graduate School of Education, University of Bristol, UK. Email: S.L.Robertson@bristol.ac.uk

This blog is based on a paper presented by the author at the Comparative and International Education Society (CIES) 2014 Annual Conference, on a NORRAG-organised panel on ‘Big data on education and the hegemony of counting’ (Tuesday 11/3/2014).

Views and opinions expressed in blogs are those of the authors and are not intended to represent the view of all NORRAG members.

Pingback : Without Theory, there are only Opinions | NORRAG NEWSBite

Pingback : The Countdown to Defining What Counts: Measurement and Education Post-2015 | NORRAG NEWSBite

It’s very good that this blog was republished. You should look at all your blogs and republish most of them as archival pieces

It’s very good that this blog was republished. You should look at all your blogs and republish most of them as archival pieces