Abidjan Principles on the Right to Education

This NORRAG Debates on the Right to Education is published by Professor Ann Skelton on the occasion of the publication of the Abidjan Principles on the human rights obligations of States to provide public education and to regulate private involvement in education. Prof. Skelton chairs the Drafting Committee of the Abidjan Principles and is a member of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child and the UNESCO Chair of Education Law in Africa.

My grandfather, the first in his family to be educated, was 13 years old when he left school and went to work in a coalmine. He was born in 1900, so it was the year 1913. He moved from Scotland to England and in the 1920s he went on to participate in the strike for a five-day week. For the next generation, it was much easier. His sons did not go to work in the mine, as the generations before had done. All his children, girls and boys, went to public schools – they received free lunch and a half a pint of milk each day. My father finished school, attended ‘night school’ and became an engineer. I too went to public school and to a public university, and am now a Law Professor. Just like that, from coal mining child labourer, to child rights Law Professor in two generations, through accessible, high quality, public education. But as I grew up in apartheid era South Africa, I soon became aware that my opportunities were available to only a few, as a discriminatory system excluded the majority, poor population from quality public education.

That is why the Abidjan Principles, published today, are so important. If all children get access to free, quality education, they can reach their full potential within their lifetimes, no matter how poor they start out. As the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights put it so powerfully in their General Comment no 13: ‘Education is the primary vehicle by which the socially and economically marginalised adults and children can lift themselves out of poverty.’

International human rights standards set out the right to education, and demand equal access to education through providing education free of charge as effectively and expeditiously as possible. In SDG 4, the majority of states have committed to providing free education at pre-primary, primary, and secondary education by 2030.

Human rights treaties also allow for the liberty to establish and maintain private educational institutions, provided that they are regulated by the state. This liberty is grounded in ideas such as freedom of religion and culture, and also protection against an authoritarian state or a neglectful state that does not provide access to education that is acceptable to individuals or groups. This origin is understandable, and its inclusion in international law instruments has created a space for non-profit education providers, many of which have good intentions and are in fact providing education for the poor and marginalized in situations where the state simply is not providing it. This, in turn, has fostered situations in some states where governments have simply reneged on their obligation to provide free quality public education for all, content to let others fill the gap. It has also created situations where commercial entities have seen a gap in what they see as a market, and sought to take advantage of this by commodifying learning and taking quality education out of the reach of the many, leaving poor children stranded in worsening public education systems. Regrettably, the standard of education in low fee private schools is not always good – so parents are not only paying for what should be provided to them free of charge, but are in many cases being short-changed.

The Abidjan Principles remind us that education is not for sale. The principles reiterate the duties of states to provide equal access to quality education, all of which may have been said before. But the principles go much further than any other document on delineating the obligations of states to regulate private education. In essence, the principles require states to impose public service obligations on private actors involved in education. States must design and enforce minimum standards with which the private actors must comply, and ensure monitoring and accountability. Financing is a difficult issue – the principles reinforce the fact that the international law does not oblige states to fund private education, and that states should rather prioritise the funding of public education. The Abidjan Principles state that public funding of private educational institutions should meet certain requirements. Notably, it should be a time-bound measure, should not create a foreseeable risk of impairing the public education system, nor allow a diversion of funds that amounts to an impermissible retrogressive measure. The Principles list the situations in which states should not fund private educational institutions – including those that are discriminatory, don’t adhere to the minimum standards, or that contribute to adverse systemic impact on the right to education. This may seem rather a tall order – but we must remember, this does not prevent these institutions from continuing to exist, it only operates against the idea of government paying them to exist.

Ultimately, the Abidjan Principles aim to remind States of their obligations – they must lift up the poorest and most marginalized children and ensure their access to quality education – in schools as good as those their own children to attend. No looking for someone else to fill the gap, no folding of hands or shrugging of shoulders about the state of the public education system, no cosying up to multi-billionaires who offer kickbacks in return for contracts or spaces to run profit-making schools.

Ultimately, the Abidjan Principles aim to remind States of their obligations – they must lift up the poorest and most marginalized children and ensure their access to quality education – in schools as good as those their own children to attend. No looking for someone else to fill the gap, no folding of hands or shrugging of shoulders about the state of the public education system, no cosying up to multi-billionaires who offer kickbacks in return for contracts or spaces to run profit-making schools.

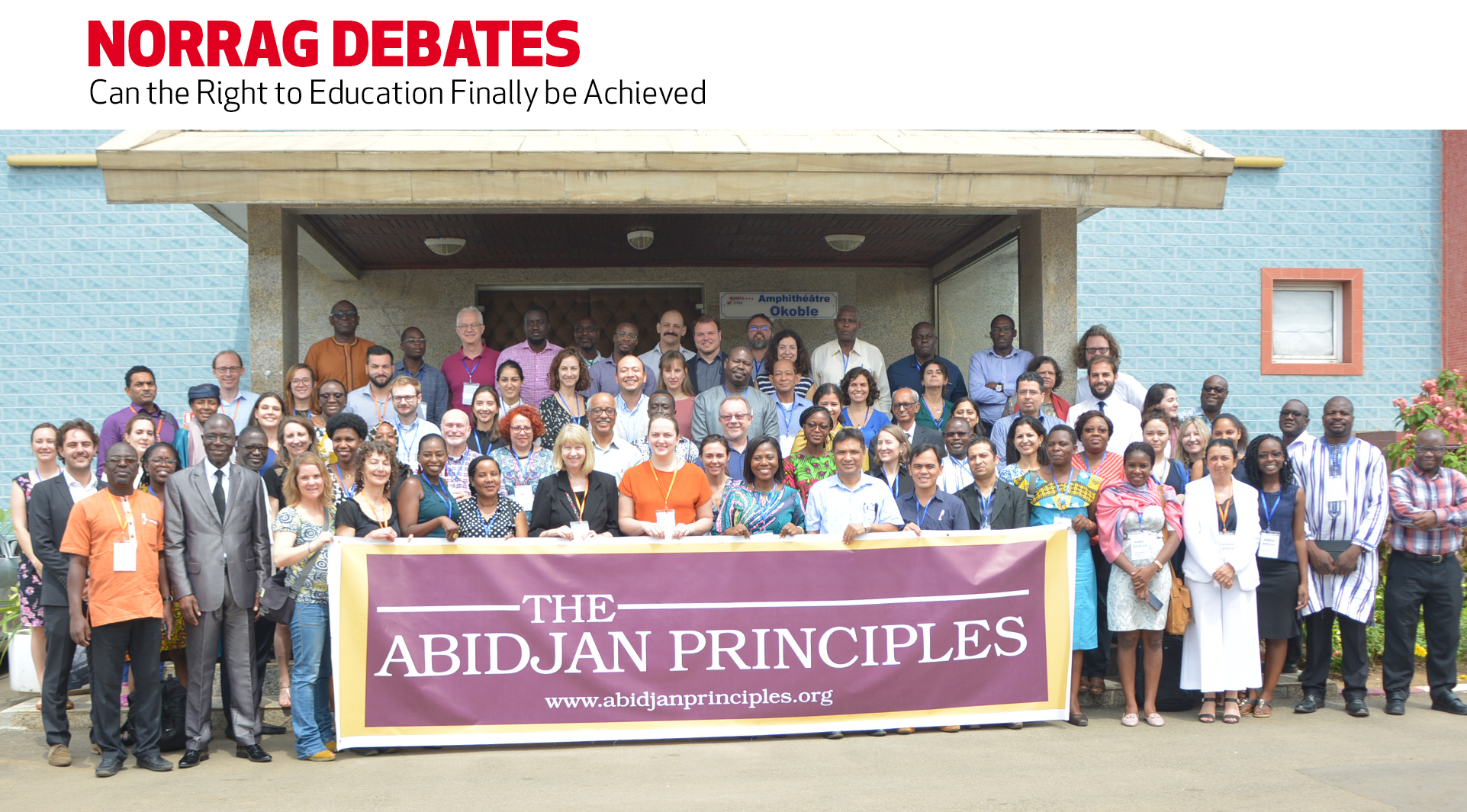

The Abidjan Principles guide States back to the basics – providing access to quality education in public schools, for all, and ensuring that the liberty to establish and maintain private educational institutions does not impede that task. The principles were drafted by a group of eminent human rights experts, which I had the honour to chair, and they provide a solid legal framework, grounded in existing international law, that will hopefully become a reference point to advance the debates on the role of the State and private actors in education. I hope that States and international organisations will seize the guidance of his new text in the fulfilment of their obligations. The hundreds of civil society organisations, citizens, and communities that have engaged in the development process of the Principles will surely use that guidance to demand accountability for the right to education.

The full text of the Abidjan Principles is available at the following link:

http://www.abidjanprinciples.org/en/principles

Contribute: The NORRAG Blog provides a platform for debate and ideas exchange for education stakeholders. Therefore if you would like to contribute to the discussion by writing your own blog post please visit our dedicated contribute page for detailed instructions on how to submit.

Disclaimer: NORRAG’s blog offers a space for dialogue about issues, research and opinion on education and development. The views and factual claims made in NORRAG posts are the responsibility of their authors and are not necessarily representative of NORRAG’s opinion, policy or activities.

Pingback : NORRAG – Abidjan Principles at the 2019 Paris Peace Forum - NORRAG -

Pingback : NORRAG –Launch of GI-ES CR Report on Transparency of Private Commercial Education Providers: A case study of Bridge International Academies - NORRAG -