Reaching the Dropped-Out Boys and the Pushed-Out Girls – A case for Open Schooling in Afghanistan

In this blogpost, Siddharth Pillai, Education Programmes Advisor for Street Child in Afghanistan, argues that Open Schooling could be a suitable model to meet the educational needs of early school leavers including the girls deprived of secondary education in Afghanistan.

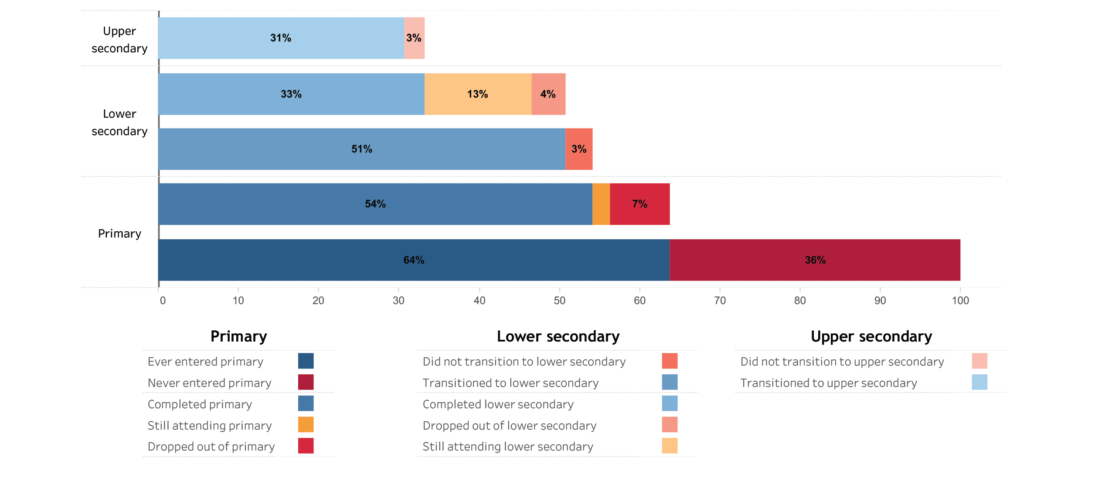

40% of Afghan children were estimated to be out of school before the restrictions were imposed by Taliban on access to secondary schools for girls [1]. Since September 2021, 80% of the school aged Afghan girls and women are out of school [2]. While there is a need to increase access to schooling for children who have never been to school, there is also a need to ensure continuity of education for those children who are at the risk of dropping out after completing primary education. UNICEF reports that out of every 100 youth aged 16-18 in Afghanistan, 64 of them ever entered primary education and a mere 31 make it to upper secondary education at the age expected for this level (see Figure 1). These figures would have drastically worsened with the restrictions on girls’ access to secondary schools.

Figure 1: Education Pathway Analysis of Afghanistan (Source: UNICEF report on Education Pathway Analysis)

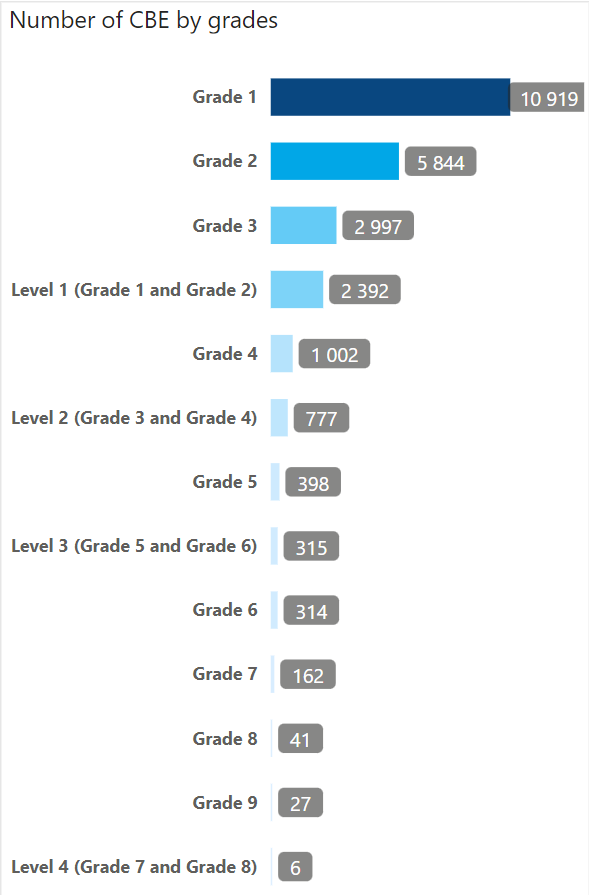

Catering mostly to the need of children who have never been to school, there are 24,000 Community Based Classes (CBEs) in Afghanistan[3] of which less than 1% cater to educational needs of children in Grade 7 and above (see Figure 2). Given the limited availability of funding and large proportion of out of school children who have never been to school, the CBE program continues to rightly focus on the lower grades. However this leaves the primary school graduates who are currently out of school due to socio-economic or political reasons without a viable pathway to continue schooling and learning.

Figure 2: Number of Community Based Classes by grades in Afghanistan (Source: CBE dashboard of Afghanistan)

Besides the blanket restrictions on Afghan girls, a large number of Afghan boys especially in remote and underserved districts[4] who complete Grade 6 fail to transition to Grade 7 or drop out due to various reasons, including the distance to the nearest lower secondary schools from their place of residence. As per the MIS data of the Ministry of Education, 12% of the districts in Afghanistan have either zero or one secondary school. In Kandahar, data shows that 40% of the districts have either zero or one secondary school. Another reason for poor transition or dropout is that adolescent children often having to support their parents in domestic work or income generating activities, do not get a chance to continue schooling due to the rigid and fixed times associated with school hours. 20% of the districts in Afghanistan have secondary school student population which is less than one fourth of its primary school student population.

Poor access to lower secondary education has been encountered in other developing countries like India[5] and one of the ways access to lower secondary education for adolescent boys and girls has been improved is through “Open Schooling”. Under such a programme, out of school children, neo-literates, and early school leavers pursue education not through the classroom teaching process but on their own, at their own pace and place supported by periodic personal contact programs for tracking progress and providing cognitive and emotional support to complete the academic tasks. In India, such learners get to continue their education to secondary and senior secondary levels. The government in such countries often have the role to enroll, examine and certify learners. The Open Schooling programme is equivalent to formal schooling and tends to have the same standard and equivalence as the courses of study of the national Board of School Education. The programme designed in such a way can offer elementary education for adolescent boys and girls from Grade 7 to Grade 9 and even beyond. This is not to disparage the importance of traditional schooling approaches but seeks to provide a ‘safety net’ or a ‘safety ladder’to those children for whom in-person schooling is not viable (dropped out boys) or acceptable to the political establishment (pushed out girls).

Distance Learning is recommended under the Community Based Education (CBE) policy of Afghanistan under Section 9.3-ICT and Distance Learning. Clause 9.3.1 states that the Ministry of Education, in coordination with implementing partners, will further develop distance learning policies. As is the case in countries like India where Open Schooling is facilitated by NGOs, Implementing Partners (IP) in Afghanistan can do the same in Afghanistan thereby preventing any significant additional workload on resource poor hub schools or provincial education directorates.

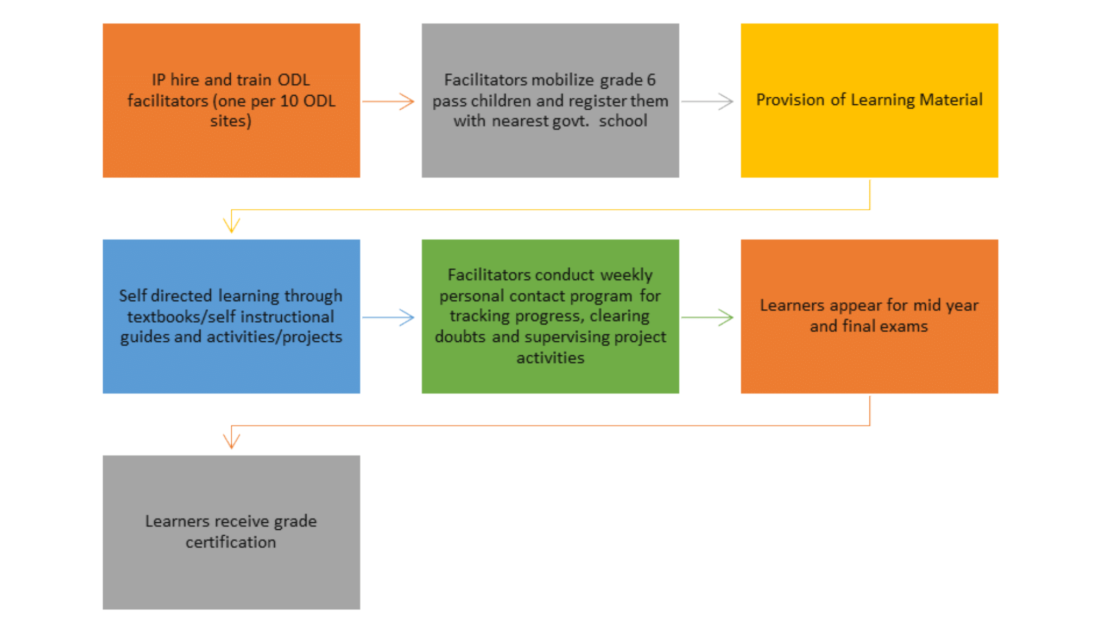

One of the proposed workflows for Open Schooling or Open Distance Learning Program (ODL) in Afghanistan is presented below:

Figure 3: Proposed workflow for Open Distance Learning Program (ODL) Program

Other elements that need to be put in place include:

Self-instructional guide for open distance learning of lower secondary school subjects: Printed self-instructional guide tightly linked to MoE endorsed textbooks can play a pivotal role in the open distance learning program. Self-instructional print-based material, which supplements the textbook, can be provided to learners so as to prepare them for summative assessments which shall lead to grade certification.

In the absence of a teacher, traditional textbooks alone may fail to ensure active learning among children as such books often focus on explanation of facts, concepts, and theories. What is required in such situations is self-instructional material that not only provides information but also:

1. Helps learner to plan her study;

2. defines what is to be learnt;

3. gives examples;

4. explains;

5. questions;

6. sets learning tasks;

7. answers learners’ questions;

8. allows learners to do self-assessment;

9. gives study advice.

As the textbook already would be available with the student, the self-instructional material needs to focus only on resources that are absent which enhances active learning and engagement with the students.

No tech/Low tech intervention to track and support student progress: A weekly personal contact program is conducted by Open Distance Learning (ODL) Facilitators at the community level so as to track the progress of learners, supervise project activities and also to clear subject specific doubts which arise in the minds of self-learners. As a low-tech intervention to further support the learners in their self-directed learning, remote check-in with the parent and learner is conducted periodically to ascertain the learner’s progress and understand the contextual barriers to help resolve them. Toll free hotlines are also often set up to clear the technical doubts of learners as well as to direct them to the relevant parts of the textbook or the guide for deeper understanding.

Monthly marked assignments: In addition to the formative assessment through in-text questions and terminal exercises provided in the self-instructional guide, monthly marked assignments are made available to the learner along with detailed answer keys which assists learners in understanding their misconceptions and self-correct them. Moreover, the preparation for the marked assignment by learner would help the latter to revisit, revise and practice what she has learnt thereby ensuring effective learning.

Community of informed and connected learners and parents: A community shura (council) comprising of the guardians of learners can be established as in Community Based Education Programmes which can meet monthly at each of the ODL sites. Shura members and guardians can be provided structure and guidance to support individual learners. Personal Contact Programs and Project Based Learning shall also be consciously used as opportunities to create a community of connected and informed learners at each ODL site leveraging the same for collaborative and peer learning.

The Ministry (de facto authority) and the Education Cluster of Afghanistan needs to further explore the opportunity for providing secondary education for boys and girls that can be possible through Open Schooling Initiative. This should include mitigating some associated risks such as authorities abdicating responsibility to continue and expand schooling facilities in underserved regions of Afghanistan. Open Schooling System contextualized for the needs of Afghanistan has the potential to meet the needs of some of the most marginalized and disadvantaged sections of the community especially girls who have been banned from accessing secondary schools. More research needs to be undertaken in Afghanistan to contextualize and adapt the existing open school models in other countries to meet the education needs of early school leavers in Afghanistan.

[1] A global initiative on out-of-school children | UNICEF Afghanistan

[2] Let girls and women in Afghanistan learn! | UNESCO

[3] Data as of 19th April, 2023

[4] Districts are identified as Hard to reach districts based on geographical proximity, conflict intensity and stakeholder complexity.

[5] Open Basic Education (OBE): The National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS)

Author

Siddharth Pillai is Education Programmes Advisor for Street Child in Afghanistan. The author would like to thank his colleagues Ramya Madhavan, Ashan Abeywardena, Hamidullah Abawi, Ilyas Qazizada and Naeem Sabawon for their support. The author can be reached at siddharth.pillai@street-child.org.