Workplace-Based Learning in South Africa: Towards System-Wide Implementation By Ronel Blom

By Ronel Blom, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

Workplace-based Learning (WBL) has been practiced in various forms in South Africa for years. However, these practices, to a large extent, have taken place in a policy vacuum. The Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET), published the White Paper on Post-School Education and Training in 2013, with the intent, amongst other things, to introduce system-wide WBL. While this is a laudable intention, it became evident in the development of a policy framework for WBL, that these practices had emerged from very different traditions, resulting in serious difficulties in achieving common principles. This blog discusses some of the barriers to achieving an approach that is fundable and could be implemented throughout the education and training system.

Workplace-based Learning (WBL) has been practiced in various forms in South Africa for years. However, these practices, to a large extent, have taken place in a policy vacuum. The Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET), published the White Paper on Post-School Education and Training in 2013, with the intent, amongst other things, to introduce system-wide WBL. While this is a laudable intention, it became evident in the development of a policy framework for WBL, that these practices had emerged from very different traditions, resulting in serious difficulties in achieving common principles. This blog discusses some of the barriers to achieving an approach that is fundable and could be implemented throughout the education and training system.

—

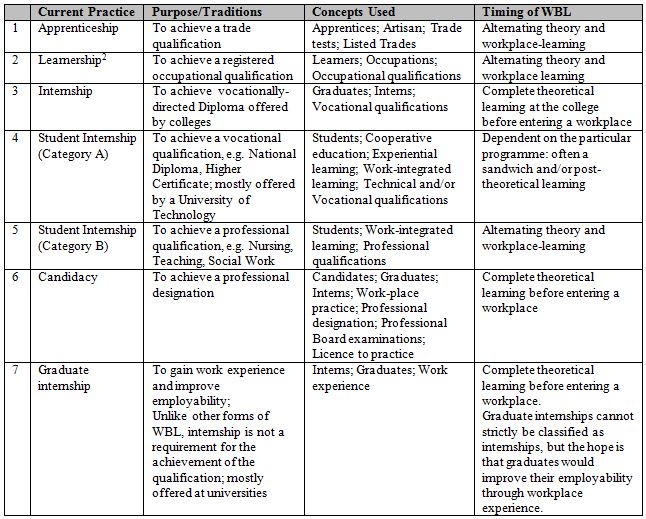

WBL is seen as an important mechanism in enhancing learning and improving the employability of graduates and diplomates[1] exiting the education and training system. This is evident from discussion of the practice in numerous education and training and other national policies, including the White Paper on Post-School Education and Training (DHET, 2013) and the widely supported National Development Plan 2030 (2012). In these policies, WBL is also mooted as a solution to youth unemployment through their exposure to, and involvement in, actual workplaces; and in boosting growth and development of the economy. However, while WBL has been widespread, there are substantial differences in practices emanating from a variety of traditions. The table below provides a brief overview of these practices, purposes, concepts and likely timing of WBL in South Africa.

Source: DHET (2015)

While the DHET intends, with the development of a policy framework for WBL, to establish common principles and practices that will enhance learning, improve employability, and enable funding and quality control, agreement on a common set of principles has been quite difficult.

These difficulties can be grouped as follows: (1) conceptual differences; (2) the status of ‘learner-workers’ when they enter the workplace; (3) the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders; (4) quality assurance arrangements; (5) (dis)incentives for employers.

- Conceptual differences

While all WBL practices are arguably about enhancing learning while the student is busy with his/her programme, it is evident that some practices lean more toward an emphasis on ‘employability’. Thus, 1, 2, 4 and 5 (see table above) are about ‘enhancing learning’ because workplace practice is undertaken in support of the curriculum; 3 and especially 7, are firmly located within the need for improved employability. Candidacy (number 6) is undertaken to achieve professional status and a licence to practice. These conceptual differences result in different practices, and consequently influence everything else that follows.

- The status of ‘learner-workers’

In some cases, aligning with the conceptual differences, the status of people entering the workplace for WBL are those of ‘students’, for example 4 and 5 (see table above). However, the rest are seen to be employees, subject to labour laws and regulations and workplace policies and procedures. The status of such people therefore impact on the contractual arrangements (including liability of the employer) and the willingness of employers to host them. This, in turn, influences the roles and responsibilities of the role players.

- Roles and responsibilities of stakeholders

In terms of roles and responsibilities, the conceptual differences have an important impact on WBL practices. First, when the purpose is ‘enhanced learning’, and the person involved is considered a ‘student’, the onus is on the institution (college or university) to ensure that their students are placed and assessed, while ‘learner-workers’ (employees) are often required to find their own opportunities for WBL. Second, the employer has very different responsibilities – if the person is a student, the workplace has to provide, at a minimum, a person who will manage the students’ time and assessment, while for ‘learner-workers’, these responsibilities are often vague or non-existent, or are aligned with requirements of professional bodies.

- Quality assurance arrangements

Where a ‘student’ is involved, the institution takes responsibility for the quality assurance of the programme, in keeping with the requirements of the college/university and their regulators. ‘Learner-workers’ however, are either subject to the quality assurance arrangements of a professional body, or not subject to any arrangements at all. The comparability in terms of quality of WBL is therefore quite problematic.

- (Dis)Incentives for employers

South African employers, for various reasons, do not have a culture of hosting students for WBL. Whereas some practices have been entrenched in the system, the bulk of graduates and diplomates find it difficult to obtain relevant workplace-based practice that will enhance their chances to gain meaningful employment. Any (or all) of the reasons discussed under the previous four points could be disincentives for employers to open up their workplaces to students.

Good intentions, but only practice will tell…

The DHET has embarked on the development of a policy framework for WBL that is intended to accommodate as many graduates and diplomates as possible for WBL in the future. However, unless the disincentives are addressed in full, it may end in a good, but un-implementable policy framework.

Dr Ronel Blom is a researcher at the Centre for Researching Education and Labour, of the University of the Witwatersrand. Email: ronel@davinci.ac.za

Reference

DHET – Department of Higher Education and Training (2015) Policy Framework on Workplace-Based Learning (still forthcoming)

[1] ‘Diplomates’ refer to successful graduates of programmes offered by the former technical colleges, which were subsequently renamed Further Education and Training Colleges and more recently (2013) again renamed Technical and Vocational Education and Training Colleges. The Diploma programmes are post-school programmes, but do not enjoy a very high status in the system. Thousands of students nevertheless undertake these studies, but struggle to achieve their final certification because of the requirement to complete workplace-based learning.

On 23rd February 2016 in Johannesburg, NORRAG and REAL, the Centre for Researching Education and Labour, of the University of the Witwatersrand are hosting a seminar to launch their newly established International Collaborative Programme of Work in education, skills and labour policies.

NORRAG (Network for International Policies and Cooperation in Education and Training) is an internationally recognised, multi-stakeholder network which has been seeking to inform, challenge and influence international education and training policies and cooperation for almost 30 years. NORRAG has more than 4,500 registered members worldwide and is free to join. Not a member? Join free here.