The Growing Gender and Educational Inequalities - Addressing the Marginalized! By Sehar Saeed and Huma Zia

By Sehar Saeed and Huma Zia, Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), Pakistan.

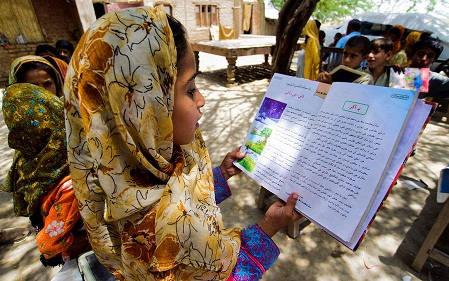

Education in itself is a fundamental human right, a bedrock of development that contributes to all social, economic and environmental dimensions, leading to gains for generations to come. The dividends that result from investments in education are immeasurable. However, for these benefits to accrue, all girls and boys must have education opportunities both in and outside of school and should be acquiring meaningful learning that leads to mastery of skills.

Education in itself is a fundamental human right, a bedrock of development that contributes to all social, economic and environmental dimensions, leading to gains for generations to come. The dividends that result from investments in education are immeasurable. However, for these benefits to accrue, all girls and boys must have education opportunities both in and outside of school and should be acquiring meaningful learning that leads to mastery of skills.

Since 2000, the efforts to achieve the MDGs have yielded unprecedented progress in both the developed and the underdeveloped countries. While growth is noticeable, the sad reality is that the achievements have been uneven; constrained by trends in demography, urbanization, health, economic and shifting global realities. More than 57 million children continue to be denied their right to primary education due to the failure to reach the marginalized (EFA Global Monitoring Report, 2013/14). Failure to address the structural disparities linked to wealth, gender, ethnicity, language, disability and other markers of disadvantage is holding back progress towards Education for All and fuelling wider processes of social exclusion. Children and adolescents from the poorest households are at least three times more likely to be out of school than children from the richest households (MDG Report, 2013).

Where economic and gender disparities are preventing millions of girls and boys from even attending school, those who are attending often leave both primary and secondary levels without acquiring the basic knowledge, skills, and competencies. According to estimates in the 2013/14 EFA Global Monitoring Report: At least 250 million primary-school-age children around the world are not able to read, write or count well enough to meet minimum learning standards, including girls and boys who have spent at least four years in school. In Pakistan, large disparities in learning achievement exist and are heavily influenced by their family backgrounds. ASER (The Annual Status of Education Report) data reflects such inequalities very clearly. Shocking results from ASER Pakistan (2012, 2013) have shown that the vast majority of pupils between 5-16 years old have not even achieved what is expected of a grade 2 student in language and mathematics. This is coupled with widespread social and gender disparities in educational outcomes reflected by creating an ASER wealth index with the help of household indicators tapped during the survey. The empirical study conducted by using ASER data set and presented in the UKFIET Conference in September 2013 demonstrated the impact of wealth status of households on the learning levels of children and thus leading to growing inequalities.

Stark Differences in Enrollment and Learning:

The ASER Pakistan (2012 and 2013) data set highlights the appalling access and gender disparities created in terms of enrollment and learning levels because of differences in wealth status. Talking in terms of access, a large proportion of households were not able to send their children to schools at all because of poverty. The percentage of out-of-school children was found to be highest in the poorest quartile (41%) as compared to the richest quartile (17%). The findings also reflect that children, particularly girls, from poor households face a much greater risk of being out of school. Fifty-three percent of females are out of school in the poorest quartile as compared to 20% females in the richest quartile. In terms of enrollment, the richest quartile again has the highest percentage of children enrolled (83%) whereas the poorest quartile has the lowest enrollment rate (59%).

Given the disparities in enrollment and out-of-school children, ASER 2013 results further strengthens the stance that socio-economic factors are adversely affecting the learning levels of children in Pakistan. Learning levels of children in all three subjects (English, Local Language and Arithmetic) increase along the wealth index towards the richest quintile. The poorest quintile has the lowest learning levels (19% Urdu/Sindhi/Pashto, 17% English, and 17% Math) while the richest quintile has the highest learning levels (43% Urdu/Sindhi/Pashto, 42% English, and 38% Math).

These results also corroborate with those of the World Inequality Database on Education (WIDE) produced by the EFA Global Monitoring Report Team at UNESCO and also confirm the findings of the 2009 PISA survey that established: “the higher the quartile of the socio economic index to which a student belonged, the better the performance, with a similar pattern for boys and girls” (EFA Global Monitoring Report, 2012).

Therefore, we believe that the education indicators associated with MDGs 2 and 3 are particularly open to critique on their limited equality focus. At a time when the global community is deeply engaged in planning post-2015 development goals, it is vital to ensure that the vision of EFA is not just limited to UPE and access but more importantly to learning with equity. Conversations in strategic forums must include marginalized and excluded groups of all ages in society. There is a dire need to include the use of metrics that go beyond standard income measures so that all countries converge not only in living standards but also in their global responsibilities to sustainable development.

Sehar Saeed & Huma Zia, Research & Policy Analyst, Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), Pakistan. Email: sahar.sd@gmail.com, humazia3@gmail.com

Pingback : Education Post-2015: Recurring Themes | NORRAG NEWSBite

Pingback : Disadvantage at the Starting Gate: Early Childhood Education in Pakistan | NORRAG NEWSBite