Refugees, Displaced Persons and Education: New Challenges for Development and for Policy

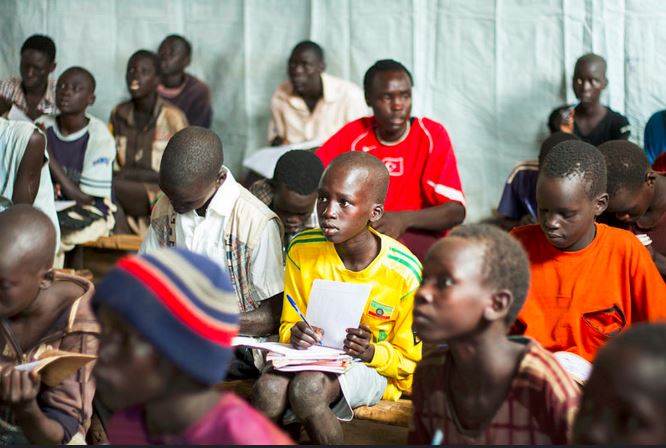

South Sudanese refugee children in their makeshift classroom, June 2014 – Kule 1 South Sudanese refugee camp Gambella, Ethiopia

When the Education for All Global Monitoring Report (GMR) of 2011 focused on The Hidden Crisis: Armed Conflict and Education, its focus was not principally with refugees at all, but with the massively deleterious effect of conflict on education. Arguably, the refugee crisis now affecting Europe has made this hidden crisis dramatically more open for Europe’s population, though this crisis has not been at all hidden for those states neighboring conflict. The World Economic Forum (WEF) of 2016 has argued that ‘top of the list of risks of highest concern …by a considerable margin, was large-scale involuntary migration’. Put another way, migration’s sudden impact on the front-line states of Europe and on the main European destinations, Germany and Sweden, has brought into the open and into focus the millions of refugees already located in refugee camps and in host communities in countries surrounding Syria, Somalia, Afghanistan, Palestine etc. In other words, the great burden of support for refugees and displaced persons has been long carried by countries of the Global South, and only sometimes with the assistance of the international relief agencies.

The next, and 53rd, issue of NORRAG News (NN53) (forthcoming in April 2016) draws attention to many different dimensions of refugees, displaced persons and education. However, it is not focused on economic migration or on migration for higher education per se, but on what the WEF calls ‘involuntary migration’ and its connections with education.

Amongst NN53’s many concerns are, firstly, the way that the sheer scale of the refugee crisis has captured Western media and political attention. The reports of the possibility of reaching Germany or Sweden have translated into a once-in-a-lifetime chance of gaining access to Europe with its perceived education, employment and welfare opportunities. By contrast in countries such as Lebanon and Jordan where one in five and one in seven persons respectively in the entire population is a refugee, the crisis caught media attention years ago.

Second, and related to the first, are questions about whether Europe’s bilateral aid agencies as well as the European Commission, the UN agencies and the World Bank will need to rethink their development cooperation to take account of the costs of supporting genuine asylum seekers in Europe. If so, this could parallel the long-standing debate about whether the imputed costs of scholarships to Southern students into countries such as Germany, Japan and France can be counted as development aid (See discussion in 2014 GMR). Will aid budgets need to be restructured to ensure that they are spent on what DFID calls the great global challenges – such as the root causes of mass migration? Will humanitarian appeals need to be rethought so that education constitutes more than the present 2%?

A related question about aid is how the countries of the Gulf as well as Iran have responded to this massive crisis in the Middle East region.

Third, there are huge differences between what can be called the protracted refugees crises such as that of the Palestinians, still located in camps around the Middle East, including in Syria, almost 70 years after their flight, on the one hand, and the expulsion of the Uganda Asians in 1972, for example, where no one has been in a camp for ages, on the other. The difference in educational expenditure is massive, since UNWRA is still supporting some 500,000 school children in its schools for Palestinians across the Middle East region as well as many as 7,000 thousand technical and vocational education and training students.

Fourth, there are a whole series of issues concerning the access to and quality of education for internally displaced people (IDPs) and for refugees. These cover lack of trained teachers, double-shift schooling, lack of security, ghettoization, language training, and lack of progression to higher education. There are larger questions about whether the poor quality of education, and the lack of access to jobs, in the first host countries is itself a driver for further migration to Europe or North America. There are other, related, issues that affect the education and training of what might be termed externally displaced persons – people that have crossed borders often for the same reasons as refugees but who have, for various reasons, not registered officially as refugees.

Fifth, the sheer scale of the Syrian crisis, on the very borders of Europe, like the Balkans before it, demands special attention. Syria, a country with a long-standing tradition of compulsory education, now has millions of its young people out of secure, full-time schooling. There is talk of a lost generation, almost the de-schooling of Syria. NN53 will report on the Syria Donor’s Conference, Supporting Syria and the Region, in London in February 2016, and its implications particularly for education.

Call for Contributions to NN53! If you would like to propose a contribution to the next issue of NORRAG News, please get in touch with the editor, Professor Kenneth King (Kenneth.king@ed.ac.uk), by mid-February 2016. The deadline for approved submissions is 14th March and we are expecting NN53 to be available on line in late March or early April 2016.

NORRAG (Network for International Policies and Cooperation in Education and Training) is an internationally recognised, multi-stakeholder network which has been seeking to inform, challenge and influence international education and training policies and cooperation for almost 30 years. NORRAG has more than 4,500 registered members worldwide and is free to join. Not a member? Join free here.

Pingback : Why the Syria Donors Conference Matters Globally | NORRAG NEWSBite

Pingback : NORRAG Why the Syria Donors Conference Matters Globally - NORRAG